In the three years since I graduated from college, people have asked about my college experience more times than I can count. For as many people who congratulated me and told me how great of a decision I made, I have had just as many people question the money I had spent and experience I had gained, putting me in the position of having to justify my choice to people who have no skin in the game.

I chose to go to a private college that after tuition, room, board, and fees cost ~$48,000 my freshman year and closer to $60,000 by the time I graduated. Even though my academic scholarship, financial aid, and college fund brought that down by half, it still left me owning a substantial amount of debt at the age of 22 with nothing but a piece of paper as collateral.

I loved my time at school and made incredible friends and memories there, but I have always struggled to articulate the actual value of it. None of my internships or jobs have come directly from my school’s ‘network’ and at this point, I have enough experience that the course work I completed and activities I participated in have been replaced by real-world work experience. After three years of reflection, I know the value of the $100,000 diploma I have lying unopened above my desk. The true value of my college education came not from the business school that I got my degree from, but rather the liberal arts education that I got to experience along the way.

A Liberal Arts Education

For those unfamiliar with it or those who have misconceptions about it, a liberal arts education is less about knowing specific things (how to amortize an asset or that carbon monoxide has a covalent bond) and more learning how to learn. It’s about critical thinking, problem-solving, and understanding how seemingly unrelated things can be connected. Hopefully, that way of thinking sparks an unquenchable thirst to continue to learn and experience things, ultimately developing into understanding them.

I saw this firsthand as an undergrad. At a school that while 85% of the students major in business, it still put a strong focus on the virtue of liberal arts. Or as they pitched it to business students, “problem-solving”. We still had tests that gauged our ability to regurgitate course material in structured formats that can be graded by machine, but the bulk of our grade was determined by projects that aimed to test our understanding of course material and how it could be applied to solve a problem.

Knowledge is a Commodity

Knowing is a binary, you either know something or you don’t. It’s easy to know how to bake cookies. It’s a lot harder to understand how the ingredients, times, and temperatures interact to give you the final product. When you understand how adjusting each individual piece controls the outcome, you’re in control.

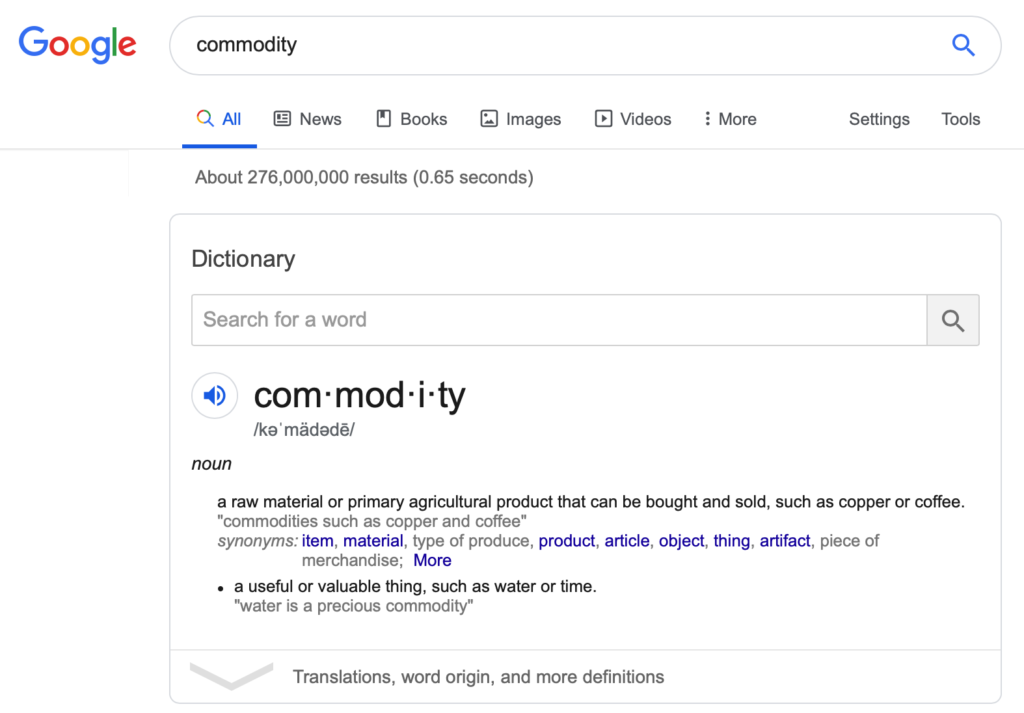

In the age of Google, knowing anything is but a few taps away. You don’t even have to know what you’re looking for exactly, as Google is better than ever at determining the intent of your search. In the age of Google it’s so easy, and tempting, to claim to be an expert in something when you can Google whatever questions you have and ‘know’ the answer in seconds.

This makes knowledge a commodity, and commodities are only as valuable as the work that goes into creating them. If it takes 0.65 seconds for Google to show you 276 million results for the search ‘commodity’ then the value of that knowledge is very low.

This is why I get concerned hearing plans about overhauling the higher education system in favor of online programs like HarvardX or Coursera. They’re heralded for their ability to democratize education. Connecting top intellectual minds with people around the world cost-efficiently. Yet, these programs fail to address the difference between knowing and understanding what is taught. It is impossible to scale subjective grading criteria when there are thousands of students to grade, relying primarily on objective grading criteria that doesn’t go past surface-level knowledge.

Understanding is Value

What this translates to in the “real world” after graduation is your value as an employee. If you work in a job that has a set throughput, meaning you know how to complete x tasks in y time period, then your value to your employer is defined as some multiplier (n) of that. But if you understand the interactions that lead to x, y, and n, you can increase your value.

For example, look at any entry-level job in marketing, like a social media coordinator. They need to come up with x posts in y time period. But, if they understand the interactions that lead to more successful posts and how social media plays into a marketing plan, they improve their value as an employee exponentially.

For the math people:

- Value of Knowledge = (x * y)*n

- Value of Understanding = ((x * y)*n)^u

Employer Priorities for College Learning

The value is recognized by companies, too. According to the Associate of American Colleges & Universities, when a description of a liberal arts education was read to employers, 74% said they “would recommend this kind of education to a young person they know as the best way to prepare for success in today’s global economy.” Additionally, 90% identified demonstration of a “capacity for continued new learning” as being an important piece of their hiring criteria.

“It’s in Apple’s DNA that technology alone is not enough. It’s technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields the results that make our hearts sing.”

— Steve Jobs (1995-2011), former CEO of Apple, Inc.